By: Rattaneeya Songsaeng & Sinith Sittirak (MISS Journal and Thai Grassroots Women Archive)

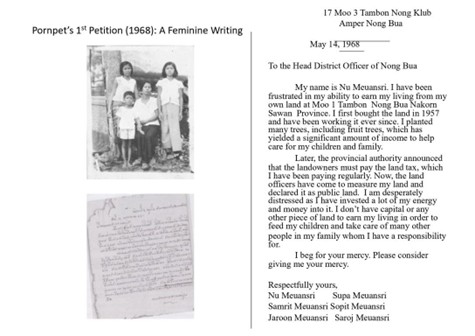

The story of Pornpet Muensri represents one of the longest land-rights struggles in Thailand’s modern history. Born in the central region (Nong Bua District, Nakhon Sawan Province), Pornpet was a farmer and a community woman. In 1968, the government officials declared her land as “state-owned public land”—one that belonged to the community where she had lived and farmed for generations. For villagers, their rights to live and work their ancestral land became precarious and uncertain. From that moment on, Pornpet began her lifelong journey for justice to reclaim her land from the state, a struggle that lasted for more than four decades. Over the years, she wrote hundreds of petitions to district officers, provincial governors, prime ministers, and members of parliament.

Pornpet was neither an activist by title nor a writer by profession. Her words, however, recorded a history of struggle, dignity, and hope. Her writings became more than just personal memories; they formed the basis of a people’s archive. Her handwriting, neat and formal at times yet rushed and full of emotion at others, hints at her persistence and exasperation as she refused to give up.

The Archival Trail

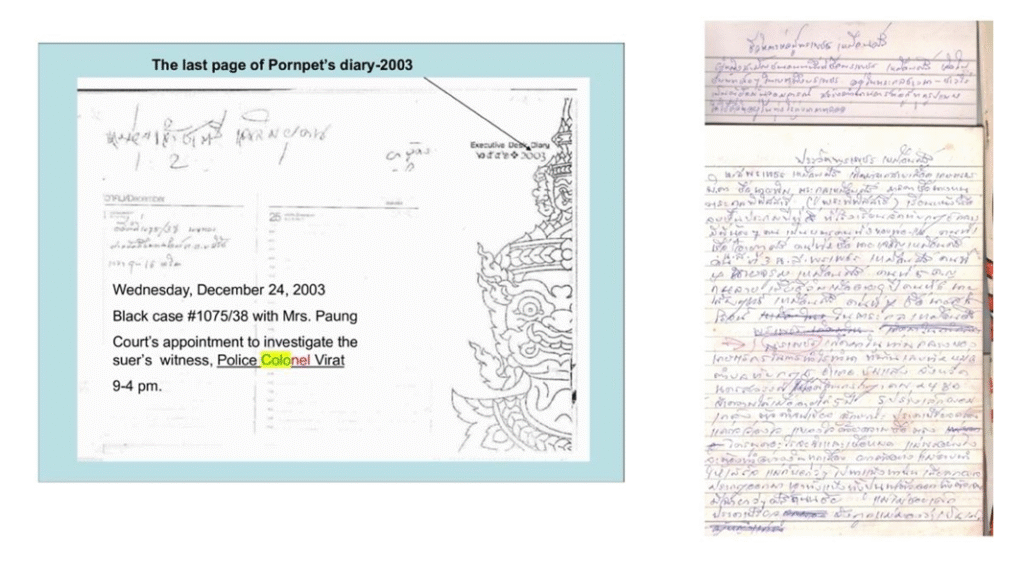

Pornpet’s archive contains one of the richest personal collections of a grassroots woman in Thailand. It consists of diaries spanning 38 years (1965–2003), over 400 petitions, court and legal documents, and an autobiography written between 2002 and 2004. Each document captures her determination to deliver the voices of rural women to the Thailand’s bureaucratic and political landscape.

Her diary entries are filled with moments of joy and exhaustion, questions about fairness, and records of meetings with officials. By negotiating, appealing, and reasoning in her own voice while mixing rural idioms with the formal style of bureaucratic writing, her petitions reveal how an ordinary peasant woman interacted with the state. As an untrained writer, Pornpet’s vernacular writing creates a form of subaltern knowledge, which turns her lived experiences into an alternative archive of life politics.

Why Pornpet’s Archives Matters

Grassroots women’s archives are rare, rich, and urgently require preservation. Pornpet Meuansri’s archive exemplifies this significance. Preserving her archive is both a feminist and political act. It affirms that writing is a form of resistance, and that the ordinary records of women’s lives have the power to reshape our understanding of history and the value of otherwise invisible experiences. Making them accessible to scholars, students, and the public does more than retrieve forgotten lives, it places marginalized women’s voices back at the forefront of historical and academic inquiry. In doing so, it contributes to decolonizing official archives and dominant modes of knowledge production.

Though her name had never appeared in textbooks, her words reveal the lived realities of injustice. Her four hundred petitions expose the sluggish, painful processes of bureaucracy, demonstrating how laws, rather then promising fairness, can instead silence the powerless. Her archive documents state violence from the perspective of a rural woman who refused to be erased. Since 1937, villagers in her area have continued to struggle with uncertainty over land rights. Pornpet’s archive keeps these struggles visible, linking past injustices to current realities. Her voice lives on through her documents, and her quest for justice still inspires new generations.

The Landscape of the Collection

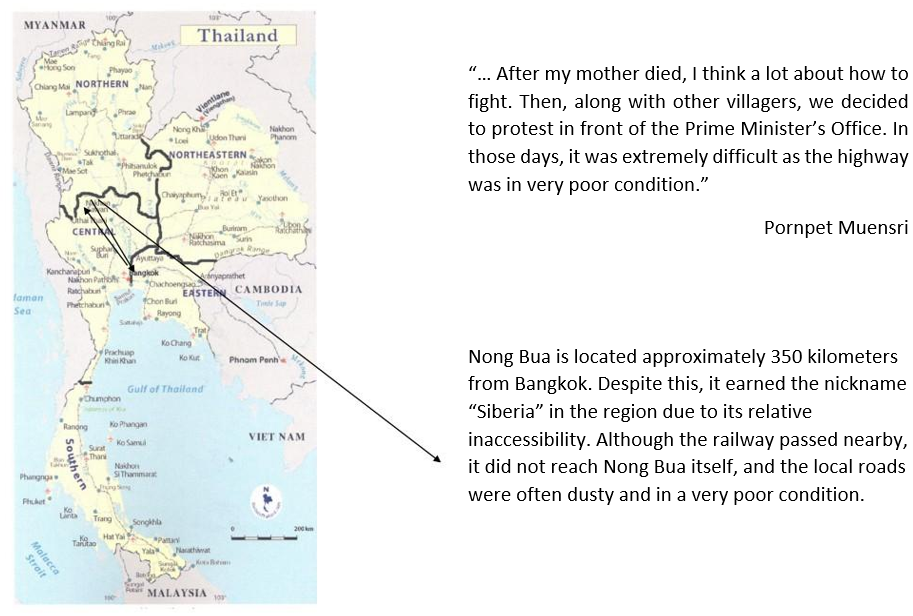

Between 2005 and 2007, during her doctoral field work, Sinith Sittirak made repeated trips from Bangkok to Nong Bua, Nakhon Sawan, to conduct fieldwork to supported Pornpet’s sister-in-law for her court case. Her journey from Bangkok to Nong Bua, Nakhon Sawan, included switching vans, riding motorcycles and tricycles. Taking local buses brought her closer to the everyday world in which Pornpet had lived and fought. Recognizing that the archive’s value extended far beyond the Meuansri family and could contribute to a broad range of humanities and social science scholarship, Sinith asked Pornpet’s brother if she could relocate the materials to Bangkok for safer storage and broader academic access.

“Please feel free to do whatever you deem appropriate,” he responded.

With that approval, Sinith and her research assistant packed the materials into fertilizer sacks and cardboard boxes and moved them to a small, rented storage room in Bangkok. The decision proved crucial, as the house where the documents had been kept was later confiscated and auctioned by the bank. Without the relocation, the archive would have been entirely lost. The Pornpet Archive is comprised of ten types of materials: diaries, petitions, legal documents, personal letters, official correspondences, court statements, maps, photographs, autobiographical writings, and miscellaneous notes. Each type opens a new window into the history of state development and women’s everyday politics between 1963 and 2004. Her diaries capture emotion and endurance; petitions trace the rhythm of state procedures.

From Archive to Practice

The preservation of Pornpet’s archive has inspired a broader feminist movement in archiving and education. The TGWAR expanded beyond preservation to become a space for learning, training, and activism.

Its work is divided into two main paths:

i) Archiving Affairs – sorting, categorizing, coding, and digitizing women’s collections; reaching out to gather critical grassroots materials that risk disappearing.

ii) Archiving Academics – This work involves teaching and training through the Summer School on Feminism, LGBTQ+, and Archival Studies. These programs help participants learn and understand feminist and archival knowledge by combining hands-on practice with theoretical foundations. They also serve as a bridge connecting memory with education and linking academic theory with the lived experiences of participants.

We also produce MISS Journal: Feminism, LGBTQ+, and Archival Studies, a publication that gathers articles, reflections, and writings from students, scholars, and contemporary authors. The journal creates a shared space where grassroots knowledge, feminist critique, and autoethnography come together, making ideas about feminism, queer perspectives, and archival studies more accessible to a wider public.

Together, these teachings and knowledge-building efforts bolster our core belief that: “every woman carries an archive within her.”

The Challenges Behind Building a Feminist Archive

Despite our feminist, philosophy-based approaches to scholarship, teaching, and archiving, building an actual archive requires professional archival knowledge, including appraising documents, organizing collections, recording metadata, and planning for long-term preservation. Our biggest challenge was clear from the start: none of our team members had formal archival training. We had to learn everything as we went, with slow progress and several interruptions due to unexpected challenges.

Since the beginning of our project, our work has relied almost solely on part-time staff and volunteers from among our Summer School students. Without full-time staff or professional archivists, the continuity of our work depends on people who join us only temporarily. With limited time and demanding academic schedules and teaching responsibilities, our core team has never had a dedicated person to oversee the archive. This means whenever a new group takes over. the process is frequently paused, restarted, and sometimes rebuilt.

Even though the technical side of the archive has progressed slowly, we have used this time to develop another important part of our work: building and sharing feminist archival knowledge. While managing the collection at a modest pace, we have also focused on turning our experiences into accessible learning resources. Through our courses, we aim to make feminist archival research understandable and approachable for a wider public.

Authors’ Biographies

Rattaneeya Songsaeng began her journey in research and activism as a volunteer at the 2024 Summer School on Feminism, Equality, and Southeast Asian Studies. She later joined MISS Journal and the Thai Grassroots Women’s Archive team. She is currently completing her BA in Southeast Asian Studies at Thammasat University and is expected to graduate in 2026.

Sinith Sittirak first discovered Pornpet’s archives in 2005 in the rural district of Nakhon Sawan. She spent more than a decade working with these materials, culminating in a PhD study titled “My ‘W/ri[gh]t/E’ and My Land’: A Postcolonial Feminist Study of Grassroots Archives and Autobiography (1937–2004), which received a National Award in 2017 and was later published. This work eventually led to the founding of the Thai Grassroots Women’s Archive and Research, a feminist archival space in honour of Pornpet’s pioneering work in documenting struggles for social justice.